Arthur Bowie Chrisman won the Newbery medal with his book Shen of the Sea "for the most distinguished contribution to American Children's literature during the year 1925." Today's critical opinion, however, wouldn't agree. Modern opinion on Goodreads.com complains about the book's lack of Chinese authenticity and potential racism. One thing I want people to note is the publisher gave the book cover the subtitle of "Chinese Stories for Children" but the actual title page simply gives a subtitle of "A Book for Children" along with crediting Else Hasselriis for her many silhouettes illustrating the book. There's no claim anywhere that the author was presenting stories from Chinese folklore. The stories should stand on their own as the creative work of a man who never traveled to China, but was fascinated with it. Yes, as one reader, Miz Lizzie, who is a folklorist on Goodreads said, "It's about as authentic as 'The Mikado' (also regarded as 'authentic' at the time)." She and some other readers further point out the better route would have been to say it was inspired by China and also to be aware of the knowledge and time when it was written. Often it is suggested by the readers that the book's stories are best read aloud. Today's story I know was particularly popular on lists of stories recommended by librarian-storytellers in the early half of the 20th century. That along with a connection with St. Louis, Missouri and this past week lead me to present it. You decide if you would tell it as NOT authentic folklore, but created by a man who clearly loved a land he had never seen. (I'll say more about St. Louis & this past week afterwards.)

AH TCHA THE SLEEPER

Years ago, in southern China, lived a boy, Ah Tcha by name. Ah Tcha was an orphan, but not according to rule. A most peculiar orphan was he. It is usual for orphans to be very, very poor. That is the world-wide custom. Ah Tcha, on the contrary, was quite wealthy. He owned seven farms, with seven times seven horses to draw the plow. He owned seven mills, with plenty of breezes to spin them. Furthermore, he owned seven thousand pieces of gold, and a fine white cat.

The farms of Ah Tcha were fertile, were wide. His horses were brisk in the furrow. His mills never lacked for grain, nor wanted for wind. And his gold was good sharp gold, with not so much as a trace of copper. Surely, few orphans have been better provided for than the youth named Ah Tcha. And what a busy person was this Ah Tcha. His bed was always cold when the sun arose. Early in the morning he went from field to field, from mill to mill, urging on the people who worked for him. The setting sun always found him on his feet, hastening from here to there, persuading his laborers to more gainful efforts. And the moon of midnight often discovered him pushing up and down the little teak-wood balls of a counting board, or else threading cash, placing coins upon a string. Eight farms, nine farms he owned, and more stout horses. Ten mills, eleven, another white cat. It was Ah Tcha’s ambition to become the richest person in the world.

They who worked for the wealthy orphan were inclined now and then to grumble. Their pay was not beggarly, but how they did toil to earn that pay which was not beggarly. It was go, and go, and go. Said the ancient woman Nu Wu, who worked with a rake in the field: “Our master drives us as if he were a fox and we were hares in the open. Round the field and round and round, hurry, always hurry.” Said Hu Shu, her husband, who bound the grain into sheaves: “Not hares, but horses. We are driven like the horses of Lung Kuan, who . . .” It’s a long story.

But Ah Tcha, approaching the murmurers, said, “Pray be so good as to hurry, most excellent Nu Wu, for the clouds gather blackly, with thunder.” And to the scowling husband he said, “Speed your work, I beg you, honorable Hu Shu, for the grain must be under shelter before the smoke of Evening Rice ascends.”

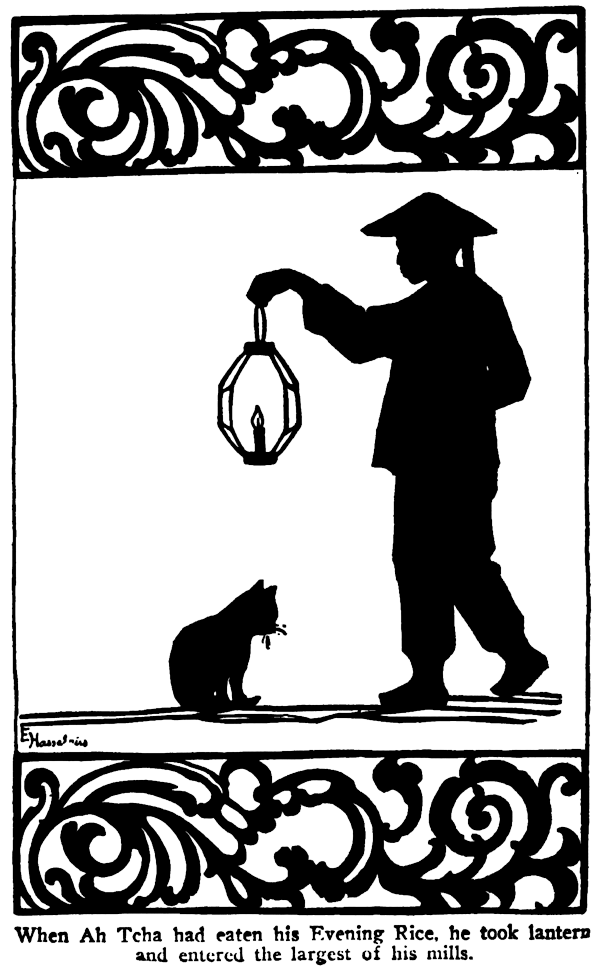

When Ah Tcha had eaten his Evening Rice, he took lantern and entered the largest of his mills. A scampering rat drew his attention to the floor. There he beheld no less than a score of rats, some gazing at him as if undecided whether to flee or continue the feast, others gnawing—and who are you, nibbling and caring not? And only a few short whisker-lengths away sat an enormous cat, sleeping the sleep of a mossy stone. The cat was black in color, black as a crow’s wing dipped in pitch, upon a night of inky darkness. That describes her coat. Her face was somewhat more black. Ah Tcha had never before seen her. She was not his cat. But his or not, he thought it a trifle unreasonable of her to sleep, while the rats held high carnival. The rats romped between her paws. Still she slept. It angered Ah Tcha. The lantern rays fell on her eyes. Still she slept. Ah Tcha grew more and more provoked. He decided then and there to teach the cat that his mill was no place for sleepy heads.

Accordingly, he seized an empty grain sack and hurled it with such exact aim that the cat was sent heels over head. “There, old Crouch-by-the-hole,” said Ah Tcha in a tone of wrath. “Remember your paining ear, and be more vigilant.” But the cat had no sooner regained her feet than she changed into . . . Nu Wu . . . changed into Nu Wu, the old woman who worked in the fields . . . a witch. What business she had in the mill is a puzzle. However, it is undoubtedly true that mills hold grain, and grain is worth money. And that may be an explanation. Her sleepiness is no puzzle at all. No wonder she was sleepy, after working so hard in the field, the day’s length through.

The anger of Nu Wu was fierce and instant. She wagged a crooked finger at Ah Tcha, screeching: “Oh, you cruel money-grubber. Because you fear the rats will eat a pennyworth of grain you must beat me with bludgeons. You make me work like a slave all day—and wish me to work all night. You beat me and disturb my slumber. Very well, since you will not let me sleep, I shall cause you to slumber eleven hours out of every dozen. . . . Close your eyes.” She swept her wrinkled hand across Ah Tcha’s face. Again taking the form of a cat, she bounded downstairs.

She had scarce reached the third step descending when Ah Tcha felt a compelling desire for sleep. It was as if he had taken gum of the white poppy flower, as if he had tasted honey of the gray moon blossom. Eyes half closed, he stumbled into a grain bin. His knees doubled beneath him. Down he went, curled like a dormouse. Like a dormouse he slumbered.

From that hour began a change in Ah Tcha’s fortune. The spell gripped him fast. Nine-tenths of his time was spent in sleep. Unable to watch over his laborers, they worked when they pleased, which was seldom. They idled when so inclined—and that was often, and long. Furthermore, they stole in a manner most shameful. Ah Tcha’s mills became empty of grain. His fields lost their fertility. His horses disappeared—strayed, so it was said. Worse yet, the unfortunate fellow was summoned to a magistrate’s yamen, there to defend himself in a lawsuit. A neighbor declared that Ah Tcha’s huge black cat had devoured many chickens. There were witnesses who swore to the deed. They were sure, one and all, that Ah Tcha’s black cat was the cat at fault. Ah Tcha was sleeping too soundly to deny that the cat was his. . . . So the magistrate could do nothing less than make the cat’s owner pay damages, with all costs of the lawsuit.

Thereafter, trials at court were a daily occurrence. A second neighbor said that Ah Tcha’s black cat had stolen a flock of sheep. Another complained that the cat had thieved from him a herd of fattened bullocks. Worse and worse grew the charges. And no matter how absurd, Ah Tcha, sleeping in the prisoner’s cage, always lost and had to pay damages. His money soon passed into other hands. His mills were taken from him. His farms went to pay for the lawsuits. Of all his wide lands, there remained only one little acre—and it was grown up in worthless bushes. Of all his goodly buildings, there was left one little hut, where the boy spent most of his time, in witch-imposed slumber.

Now, near by in the mountain of Huge Rocks Piled, lived a greatly ferocious loong, or, as foreigners would say, a dragon. This immense beast, from tip of forked tongue to the end of his shadow, was far longer than a barn. With the exception of length, he was much the same as any other loong. His head was shaped like that of a camel. His horns were deer horns. He had bulging rabbit eyes, a snake neck. Upon his many ponderous feet were tiger claws, and the feet were shaped very like sofa cushions. He had walrus whiskers, and a breath of red-and-blue flame. His voice was like the sound of a hundred brass kettles pounded. Black fish scales covered his body, black feathers grew upon his limbs. Because of his color he was sometimes called Oo Loong. From that it would seem that Oo means neither white nor pink.

The black loong was not regarded with any great esteem. His habit of eating a man—two men if they were little—every day made him rather unpopular. Fortunately, he prowled only at night. Those folk who went to bed decently at nine o’clock had nothing to fear. Those who rambled well along toward midnight, often disappeared with a sudden and complete thoroughness.

As every one knows, cats are much given to night skulking. The witch cat, Nu Wu, was no exception. Midnight often found her miles afield. On such a midnight, when she was roving in the form of a hag, what should approach but the black dragon. Instantly the loong scented prey, and instantly he made for the old witch.

There followed such a chase as never was before on land or sea. Up hill and down dale, by stream and wood and fallow, the cat woman flew and the dragon coursed after. The witch soon failed of breath. She panted. She wheezed. She stumbled on a bramble and a claw slashed through her garments. Too close for comfort. The harried witch changed shape to a cat, and bounded off afresh, half a li at every leap. The loong increased his pace and soon was close behind, gaining. For a most peculiar fact about the loong is that the more he runs the easier his breath comes, and the swifter grows his speed. Hence, it is not surprising that his fiery breath was presently singeing the witch cat’s back.

In a twinkling the cat altered form once more, and as an old hag scuttled across a turnip field. She was merely an ordinarily powerful witch. She possessed only the two forms—cat and hag. Nor did she have a gift of magic to baffle or cripple the hungry black loong. Nevertheless, the witch was not despairing. At the edge of the turnip field lay Ah Tcha’s miserable patch of thick bushes. So thick were the bushes as to be almost a wall against the hag’s passage. As a hag, she could have no hope of entering such a thicket. But as a cat, she could race through without hindrance. And the dragon would be sadly bothered in following. Scheming thus, the witch dashed under the bushes—a cat once more.

Ah Tcha was roused from slumber by the most outrageous noise that had ever assailed his ears. There was such a snapping of bushes, such an awful bellowed screeching that even the dead of a century must have heard. The usually sound-sleeping Ah Tcha was awakened at the outset. He soon realized how matters stood—or ran. Luckily, he had learned of the only reliable method for frightening off the dragon. He opened his door and hurled a red, a green, and a yellow firecracker in the monster’s path.

In through his barely opened door the witch cat dragged her exhausted self. “I don’t see why you couldn’t open the door sooner,” she scolded, changing into a hag. “I circled the hut three times before you had the gumption to let me in.”

“I am very sorry, good mother. I was asleep.” From Ah Tcha.

“Well, don’t be so sleepy again,” scowled the witch, “or I’ll make you suffer. Get me food and drink.”

“Again, honored lady, I am sorry. So poor am I that I have only water for drink. My food is the leaves and roots of bushes.”

“No matter. Get what you have—and quickly.”

Ah Tcha reached outside the door and stripped a handful of leaves from a bush. He plunged the leaves into a kettle of hot water and signified that the meal was prepared. Then he lay down to doze, for he had been awake fully half a dozen minutes and the desire to sleep was returning stronger every moment.

The witch soon supped and departed, without leaving so much as half a “Thank you.” When Ah Tcha awoke again, his visitor was gone. The poor boy flung another handful of leaves into his kettle and drank quickly. He had good reason for haste. Several times he had fallen asleep with the cup at his lips—a most unpleasant situation, and scalding. Having taken several sips, Ah Tcha stretched him out for a resumption of his slumber. Five minutes passed . . . ten minutes . . . fifteen. . . . Still his eyes failed to close. He took a few more sips from the cup and felt more awake than ever.

“I do believe,” said Ah Tcha, “that she has thanked me by bewitching my bushes. She has charmed the leaves to drive away my sleepiness.”

And so she had. Whenever Ah Tcha felt tired and sleepy—and at first that was often—he had only to drink of the bewitched leaves. At once his drowsiness departed. His neighbors soon learned of the bushes that banished sleep. They came to drink of the magic brew. There grew such a demand that Ah Tcha decided to set a price on the leaves. Still the demand continued. More bushes were planted. Money came.

Throughout the province people called for “the drink of Ah Tcha.” In time they shortened it by asking for “Ah Tcha’s drink,” then for “Tcha’s drink,” and finally for “Tcha.”

And that is its name at present, “Tcha,” or “Tay,” or “Tea,” as some call it. And one kind of Tea is still called “Oo Loong”—“Black Dragon.”

If you believe the popular tales, more new American foods were invented at the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, than during any other single event in history. The list includes the hamburger, the hot dog, peanut butter, iced tea, the club sandwich, cotton candy, and the ice cream cone, to name just a few. If all the pop histories and internet stories have it right, American foodways would be almost unrecognizable if the 1904 fair had not been held.

That picture from the Library of Congress collection shows it as the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, which is the official name. The link takes you to a Wikipedia article with a wonderful section on the "Legacy" from the event. Yes, it, too, talks about the food, but being born and growing up in St. Louis it was the buildings, originally expected to be temporary, that remain important to me. I didn't realize the administration building for Washington University in St. Louis was a fair building. Some of the fair's "legacy" went to other locations, but a separate article on Forest Park, where the fair was held, tells even more about that legacy. Yes, I learned things in both articles as I grew up close enough to hear the Zoo's lions and tigers on an early morning before traffic drowned them out. I remembered the aviary cage you could walk through dating back to the Exposition. The park's buildings and other features include some I erroneously attributed to the fair, such as the Jewel Box and its Floral Clock (built in the 1930s and the clock is a memorial to Korean War military dead). Some were correct, such as the waterfall known as The Cascades where I'm in a family picture dating back to my preschool years. One of those correct, is the Art Museum. I loved it so much I often saved lunch and bus money to buy art postcards there. Instead I said goodbye to the statue out front of the Apotheosis of St. Louis before starting the long hike home. I didn't know it was a bronze replica of a plaster statue at the fair -- nor the lawsuit by the original statue's sculptor (copyright issues even in 1906!). It was indeed presented by the Exposition in remembrance of the fair. I also didn't know things like the Exposition's "Bullfight Riot" and forgot the statue of King Louis IX, the namesake of the city, has had his sword stolen so often it's "considered a rite of passage for students in the engineering program at nearby Washington University."

It was for me a landmark deserving that "goodbye...before starting the long hike home." Thank you for joining me on this trip back in time.

|

- There are many online resources for Public Domain stories, maybe none for folklore is as ambitious as fellow storyteller, Yoel Perez's database, Yashpeh, the International Folktales Collection. I have long recommended it and continue to do so. He has loaded Stith Thompson's Motif Index into his server as a database so you can search the whole 6 volumes for whatever word or expression you like by pressing one key. http://folkmasa.org/motiv/motif.htm

- You may have noticed I'm no

longer certain Dr. Perez has the largest database, although his

offering the Motif Index certainly qualifies for those of us seeking

specific types of stories. There's another site, FairyTalez

claiming to be the largest, with "over 2000 fairy tales,

folktales, and fables" and they are "fully optimized for

phones, tablets, and PCs", free and presented without ads.

Between those two sites, there is much for story-lovers, but as they say in infomercials, "Wait, there's more!"

- Zalka Csenge Virag - http://multicoloreddiary.blogspot.com doesn't give the actual stories, but her recommendations, working her way through each country on a continent, give excellent ideas for finding new books and stories to love and tell.

You're going to find many of the links on these sites have gone down, BUT go to the Internet Archive Wayback Machine to find some of these old links. Tim's site, for example, is so huge probably updating it would be a full-time job. In the case of Story-Lovers, it's great that Jackie Baldwin set it up to stay online as long as it did after she could no longer maintain it. Possibly searches maintained it. Unfortunately Storytell list member, Papa Joe is on both Tim Sheppard's site and Story-Lovers, but he no longer maintains his old Papa Joe's Traveling Storytelling Show website and his Library (something you want to see!) is now only on the Wayback Machine. It took some patience working back through claims of snapshots but finally in December of 2006 it appears!

No comments:

Post a Comment