Snow has been keeping us and a large portion of the United States busy shoveling and plowing. This is my attitude about it: Bah Humbug!

At the same time I know that "Snow Days" as well as concern for bitter wind chills have made many children happy even if their time out doors has required bundling up and being careful not to get frostbitten.

As a result I just had to find an appropriate story. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote the perfect one about how adults just don't see things from the same way.

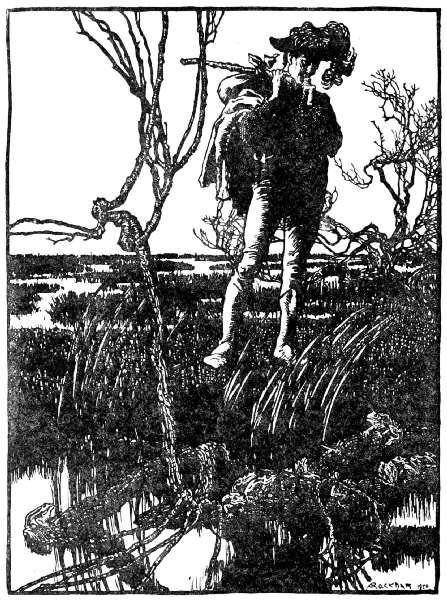

Literary tales can be hard to tell, but the Skinner sisters, Ada and Eleanor, in their winter anthology, The Pearl Story Book, did a good start with their abridgement of the story. At the same time Project Gutenberg has a well-illustrated version of it in The Snow Image: A Childish Miracle. I'm going to insert the illustrations by Marcus Waterman in their appropriate places in the Skinner version of the story.

I leave it up to you as to how you might further adapt the story while keeping the "childish miracle" of the story alive.

THE SNOW-IMAGE

Nathaniel Hawthorne

One afternoon of a cold winter’s day, when

the sun shone forth with chilly brightness,

after a long storm, two children asked leave

of their mother to run out and play in the new-fallen

snow.

The elder child was a little girl, whom, because

she was of a tender and modest disposition,

and was thought to be very beautiful,

her parents, and other people who were familiar

with her, used to call Violet.

But her brother was known by the title of

Peony, on account of the ruddiness of his

broad and round little phiz, which made

everybody think of sunshine and great scarlet

flowers.

“Yes, Violet—yes, my little Peony,” said

their kind mother; “you may go out and play

in the new snow.”

Forth sallied the two children, with a hop-skip-and-jump, that carried them at once into

the very heart of a huge snow-drift, whence

Violet emerged like a snow bunting, while

little Peony floundered out with his round face

in full bloom.

Then what a merry time they had! To

look at them, frolicking in the wintry garden,

you would have thought that the dark and

pitiless storm had been sent for no other purpose

but to provide a new plaything for Violet

and Peony; and that they themselves had been

created, as the snowbirds were, to take delight

only in the tempest and in the white mantle

which it spread over the earth.

At last, when they had frosted one another

all over with handfuls of snow, Violet, after

laughing heartily at little Peony’s figure, was

struck with a new idea.

“You look exactly like a snow-image,

Peony,” said she, “if your cheeks were not so

red. And that puts me in mind! Let us make

an image out of snow—an image of a little

girl—and it shall be our sister, and shall run

about and play with us all winter long. Won’t

it be nice?”

“Oh, yes!” cried Peony, as plainly as he

could speak, for he was but a little boy. “That

will be nice! And mamma shall see it.”

“Yes,” answered Violet; “mamma shall see

the new little girl. But she must not make

her come into the warm parlour, for, you

know, our little snow-sister will not love the

warmth.”

And forthwith the children began this great

business of making a snow-image that should

run about; while their mother, who was knitting

at the window and overheard some of

their talk, could not help smiling at the gravity

with which they set about it. They really

seemed to imagine that there would be no difficulty

whatever in creating a live little girl

out of the snow.

Indeed, it was an exceedingly pleasant sight—those

bright little souls at their task!

Moreover, it was really wonderful to observe

how knowingly and skillfully they managed

the matter. Violet assumed the chief direction,

and told Peony what to do, while, with

her own delicate fingers, she shaped out all

the nicer parts of the snow-figure.

It seemed, in fact, not so much to be made

by the children, as to grow up under their

hands, while they were playing and prattling

about it. Their mother was quite surprised at

this, and the longer she looked, the more and

more surprised she grew.

Now, for a few moments, there was a busy

and earnest but indistinct hum of the two

children’s voices, as Violet and Peony

wrought together with one happy consent.

Violet still seemed to be the guiding spirit,

while Peony acted rather as a labourer and

brought her the snow from far and near. And

yet the little urchin evidently had a proper

understanding of the matter, too.

“Peony, Peony!” cried Violet; for her

brother was at the other side of the garden.

“Bring me those light wreaths of snow that

have rested on the lower branches of the pear-tree.

You can clamber on the snow-drift,

Peony, and reach them easily. I must have

them to make some ringlets for our snow-sister’s

head!”

“Here they are, Violet!” answered the

little boy. “Take care you do not break them. Well done! Well done! How pretty!”

“Does she not look sweet?” said Violet, with

a very satisfied tone; “and now we must have

some little shining bits of ice to make the

brightness of her eyes. She is not finished yet.

Mamma will see how very beautiful she is;

but papa will say, ‘Tush! nonsense! come in

out of the cold!’”

“Let us call mamma to look out,” said

Peony; and then he shouted, “Mamma!

mamma!! mamma!!! Look out and see what

a nice ’ittle girl we are making!”

“What a nice playmate she will be for us

all winter long!” said Violet. “I hope papa

will not be afraid of her giving us a cold!

Sha’n’t you love her dearly, Peony?”

“Oh, yes!” cried Peony. “And I will hug

her and she shall sit down close by me and

drink some of my warm milk.”

“Oh, no, Peony!” answered Violet, with

grave wisdom. “That will not do at all.

Warm milk will not be wholesome for our

little snow-sister. Little snow-people like her

eat nothing but icicles. No, no, Peony; we

must not give her anything warm to drink!”

There was a minute or two of silence; for

Peony, whose short legs were never weary,

had gone again to the other side of the garden.

All of a sudden, Violet cried out, loudly and

joyfully, “Look here, Peony! Come quickly!

A light has been shining on her cheek out of

that rose-coloured cloud! And the colour does

not go away! Is not that beautiful?”

“Yes, it is beau-ti-ful,” answered Peony,

pronouncing the three syllables with deliberate

accuracy. “O Violet, only look at her

hair! It is all like gold!”

“Oh, certainly,” said Violet, as if it were

very much a matter of course. “That colour,

you know, comes from the golden clouds that

we see up there in the sky. She is almost

finished now. But her lips must be made very

red, redder than her cheeks. Perhaps, Peony,

it will make them red if we both kiss them!”

Accordingly, the mother heard two smart

little smacks, as if both her children were

kissing the snow-image on its frozen mouth.

But, as this did not seem to make the lips quite

red enough, Violet next proposed that the

snow-child should be invited to kiss Peony’s scarlet cheek. “Come, ’ittle snow-sister, kiss

me!” cried Peony.

“There! she has kissed you,” added Violet,

“and now her lips are very red. And she

blushed a little, too!”

“Oh, what a cold kiss!” cried Peony.

Just then, there came a breeze of the pure

west wind sweeping through the garden and

rattling the parlour-windows. It sounded so

wintry cold, that the mother was about to tap

on the window-pane with her thimbled finger,

to summon the two children in, when they

both cried out to her with one voice:

“Mamma! mamma! We have finished our

little snow-sister, and she is running about the

garden with us!”

“What imaginative little beings my children

are!” thought the mother, putting the last few

stitches into Peony’s frock. “And it is strange,

too, that they make me almost as much a child

as they themselves are! I can hardly help

believing now that the snow-image has really

come to life!”

“Dear mamma!” cried Violet, “pray look

out and see what a sweet playmate we have!”

The mother, being thus entreated, could no

longer delay to look forth from the window.

The sun was now gone out of the sky, leaving,

however, a rich inheritance of his brightness

among those purple and golden clouds

which make the sunsets of winter so magnificent.

But there was not the slightest gleam or

dazzle, either on the window or on the snow;

so that the good lady could look all over the

garden, and see everything and everybody in

it. And what do you think she saw there?

Violet and Peony, of course, her own two

darling children.

Ah, but whom or what did she see besides?

Why, if you will believe me, there was a small

figure of a girl, dressed all in white, with rose-tinged

cheeks and ringlets of golden hue, playing

about the garden with the two children!

A stranger though she was, the child seemed

to be on as familiar terms with Violet and

Peony, and they with her, as if all the three

had been playmates during the whole of their

little lives. The mother thought to herself

that it must certainly be the daughter of one of the neighbours, and that, seeing Violet and

Peony in the garden, the child had run across

the street to play with them.

So this kind lady went to the door, intending

to invite the little runaway into her comfortable

parlour; for, now that the sunshine

was withdrawn, the atmosphere out of doors

was already growing very cold.

But, after opening the house-door, she

stood an instant on the threshold, hesitating

whether she ought to ask the child to come in,

or whether she should even speak to her. Indeed,

she almost doubted whether it were a

real child, after all, or only a light wreath of

the new-fallen snow, blown hither and thither

about the garden by the intensely cold west

wind.

There was certainly something very singular

in the aspect of the little stranger.

Among all the children of the neighbourhood

the lady could remember no such face, with

its pure white and delicate rose-colour, and the

golden ringlets tossing about the forehead and

cheeks.

And as for her dress, which was entirely of

white, and fluttering in the breeze, it was

such as no reasonable woman would put upon

a little girl when sending her out to play in

the depth of winter. It made this kind and

careful mother shiver only to look at those

small feet, with nothing in the world on them

except a very thin pair of white slippers.

Nevertheless, airily as she was clad, the

child seemed to feel not the slightest inconvenience

from the cold, but danced so lightly

over the snow that the tips of her toes left

hardly a print in its surface; while Violet

could but just keep pace with her, and

Peony’s short legs compelled him to lag behind.

All this while, the mother stood on the

threshold, wondering how a little girl could

look so much like a flying snow-drift, or how

a snow-drift could look so very like a little

girl.

She called Violet and whispered to her.

“Violet, my darling, what is this child’s

name?” asked she. “Does she live near us?”

“Why, dearest mamma,” answered Violet,

laughing to think that her mother did not comprehend so very plain an affair, “this is

our little snow-sister whom we have just been

making!”

“Yes, dear mamma,” cried Peony, running

to his mother, and looking up simply into her

face. “This is our snow-image! Is it not a

nice ’ittle child?”

“Violet,” said her mother, greatly perplexed,

“tell me the truth, without any jest.

Who is this little girl?”

“My darling mamma,” answered Violet,

looking seriously into her mother’s face, surprised

that she should need any further explanation,

“I have told you truly who she is.

It is our little snow-image which Peony and I

have been making. Peony will tell you so, as

well as I.”

“Yes, mamma,” declared Peony, with much

gravity in his crimson little phiz, “this is ’ittle

snow-child. Is not she a nice one? But,

mamma, her hand is, oh, so very cold!”

While mamma still hesitated what to think

and what to do, the street-gate was thrown

open, and the father of Violet and Peony appeared,

wrapped in a pilot-cloth sack, with a

fur cap drawn down over his ears, and the

thickest of gloves upon his hands.

Mr. Lindsey was a middle-aged man, with

a weary and yet a happy look in his wind-flushed

and frost-pinched face, as if he had

been busy all day long, and was glad to get

back to his quiet home. His eyes brightened

at the sight of his wife and children, although

he could not help uttering a word or two of

surprise at finding the whole family in the

open air, on so bleak a day, and after sunset,

too.

He soon perceived the little white stranger,

sporting to and fro in the garden, like a dancing

snow-wreath and the flock of snowbirds

fluttering about her head.

“Pray, what little girl may this be?” inquired

this very sensible man. “Surely her

mother must be crazy, to let her go out in such

bitter weather as it has been today, with only

that flimsy white gown and those thin slippers!”

“My dear husband,” said his wife, “I know

no more about the little thing than you do.

Some neighbour’s child, I suppose. Our Violet

and Peony,” she added, laughing at herself

for repeating so absurd a story, “insist that

she is nothing but a snow-image which they

have been busy about in the garden, almost all

the afternoon.”

As she said this, the mother glanced her

eyes toward the spot where the children’s

snow-image had been made. What was her

surprise on perceiving that there was not the

slightest trace of so much labour!—no image

at all!—no piled-up heap of snow!—nothing

whatever, save the prints of little footsteps

around a vacant space!

“This is very strange!” said she.

“What is strange, dear mother?” asked

Violet. “Dear father, do not you see how it

is? This is our snow-image, which Peony and

I have made, because we wanted another playmate.

Did not we, Peony?”

“Yes, papa,” said crimson Peony. “This is

our ’ittle snow-sister. Is she not beau-ti-ful?

But she gave me such a cold kiss!”

“Pooh, nonsense, children!” cried their good

honest father, who had a plain, sensible way

of looking at matters. “Do not tell me of

making live figures out of snow. Come, wife;

this little stranger must not stay out in the

bleak air a moment longer. We will bring her

into the parlour; and you shall give her a

supper of warm bread and milk, and make her

as comfortable as you can.”

So saying, this honest and very kind-hearted

man was going toward the little damsel, with

the best intentions in the world. But Violet

and Peony, each seizing their father by the

hand, earnestly besought him not to make her

come in.

“Nonsense, children, nonsense, nonsense!”

cried the father, half-vexed, half-laughing.

“Run into the house, this moment! It is too

late to play any longer now. I must take care

of this little girl immediately, or she will catch

her death of cold.”

And so, with a most benevolent smile, this

very well-meaning gentleman took the snow-child

by the hand and led her toward the

house.

She followed him, droopingly and reluctant,

for all the glow and sparkle were gone out

of her figure; and, whereas just before she had

resembled a bright, frosty, star-gemmed evening,

with a crimson gleam on the cold horizon,

she now looked as dull and languid as a

thaw.

As kind Mr. Lindsey led her up the steps of

the door, Violet and Peony looked into his

face, their eyes full of tears which froze before

they could run down their cheeks, and

again entreated him not to bring their snow-image

into the house.

“Not bring her in!” exclaimed the kind-hearted

man. “Why, you are crazy, my

little Violet!—quite crazy, my small Peony!

She is so cold already that her hand has

almost frozen mine, in spite of my thick

gloves. Would you have her freeze to

death?”

His wife, as he came up the steps, had been

taking another long, earnest gaze at the little

white stranger. She hardly knew whether it

was a dream or no; but she could not help

fancying that she saw the delicate print of

Violet’s fingers on the child’s neck. It looked

just as if, while Violet was shaping out the

image, she had given it a gentle pat with her

hand, and had neglected to smooth the impression

quite away.

“After all, husband,” said the mother, “after

all, she does look strangely like a snow-image!

I do believe she is made of snow!”

A puff of the west wind blew against the

snow-child, and again she sparkled like a

star.

“Snow!” repeated good Mr. Lindsey, drawing

the reluctant guest over his hospitable

threshold. “No wonder she looks like snow.

She is half frozen, poor little thing! But a

good fire will put everything to rights.”

This common-sensible man placed the snow-child

on the hearth-rug, right in front of the

hissing and fuming stove.

“Now she will be comfortable!” cried Mr.

Lindsey, rubbing his hands and looking about

him, with the pleasantest smile you ever saw.

“Make yourself at home, my child.”

Sad, sad and drooping, looked the little

white maiden as she stood on the hearth-rug,

with the hot blast of the stove striking through

her like a pestilence. Once she threw a glance

toward the window, and caught a glimpse,

through its red curtains, of the snow-covered

roofs and the stars glimmering frostily, and all

the delicious intensity of the cold night. The

bleak wind rattled the window-panes as if it

were summoning her to come forth. But

there stood the snow-child, drooping, before

the hot stove!

But the common-sensible man saw nothing

amiss.

“Come, wife,” said he, “let her have a pair

of thick stockings and a woolen shawl or

blanket directly; and tell Dora to give her

some warm supper as soon as the milk boils.

You, Violet and Peony, amuse your little

friend. She is out of spirits, you see, at finding

herself in a strange place. For my part, I

will go around among the neighbours and find

out where she belongs.”

The mother, meanwhile, had gone in search

of the shawl and stockings. Without heeding

the remonstrance of his two children, who

still kept murmuring that their little snow-sister

did not love the warmth, good Mr.

Lindsey took his departure, shutting the parlour

door carefully behind him.

Turning up the collar of his sack over his

ears, he emerged from the house, and had

barely reached the street-gate, when he was

recalled by the screams of Violet and Peony

and the rapping of a thimbled finger against

the parlour window.

“Husband! husband!” cried his wife, showing

her horror-stricken face through the

window panes. “There is no need of going

for the child’s parents!”

“We told you so, father!” screamed Violet

and Peony, as he re-entered the parlour. “You

would bring her in; and now our poor—dear—beau-ti-ful

little snow-sister is thawed!”

And their own sweet little faces were already

dissolved in tears; so that their father,

seeing what strange things occasionally happen

in this every-day world, felt not a little anxious

lest his children might be going to thaw too.

In the utmost perplexity, he demanded an

explanation of his wife. She could only reply

that, being summoned to the parlour by cries

of Violet and Peony, she found no trace of

the little white maiden, unless it were the remains

of a heap of snow, which, while she

was gazing at it, melted quite away upon the

hearth-rug.

“And there you see all that is left of it!”

added she, pointing to a pool of water, in front

of the stove.

“Yes, father,” said Violet, looking reproachfully

at him through her tears, “there

is all that is left of our dear little snow-sister!”

“Naughty father!” cried Peony, stamping

his foot, and—I shudder to say—shaking his

little fist at the common-sensible man. “We

told you how it would be! What for did you

bring her in?”

And the stove, through the isinglass of

its door, seemed to glare at good Mr. Lindsey,

like a red-eyed demon, triumphing in the mischief

which it had done! (Abridged.)

******

May both children and adults survive this snowy, cold time and eventually see spring.

****************

This is part of a

series of postings of stories under the category, “Keeping the

Public in Public Domain.” The idea behind Public Domain was to

preserve our cultural heritage after the authors and their immediate

heirs were compensated. I feel strongly current copyright law delays

this intent on works of the 20th century. My own library

of folklore includes so many books within the Public Domain I decided

to share stories from them. I hope you enjoy discovering them.

At

the same time, my own involvement in storytelling regularly creates

projects requiring research as part of my sharing stories with an

audience. Whenever that research needs to be shown here, the

publishing of Public Domain stories will not occur that week.

This is a return to my regular posting of a research project here.

(Don't worry, this isn't dry research, my research is always geared

towards future storytelling to an audience.) Response has

convinced me that "Keeping the Public in Public Domain"

should continue along with my other postings as often as I can manage

it.

See the sidebar for other Public

Domain story resources I recommend on the page “Public Domain Story Resources."

.jpg)